Rote Memorization is Taboo … but is it really that bad?

Editor Adam Kardos

In recent decades there has been a trend in education towards critical thinking and learning through discovery. Education systems around the world are trying to find ways to create students who are independent thinkers, who can think outside of the box. For many, learning by rote memorization is considered out of date. Education that focuses on rote learning is seen as producing students who are skilled at regurgitating information but not able to manipulate and synthesize such information effectively.

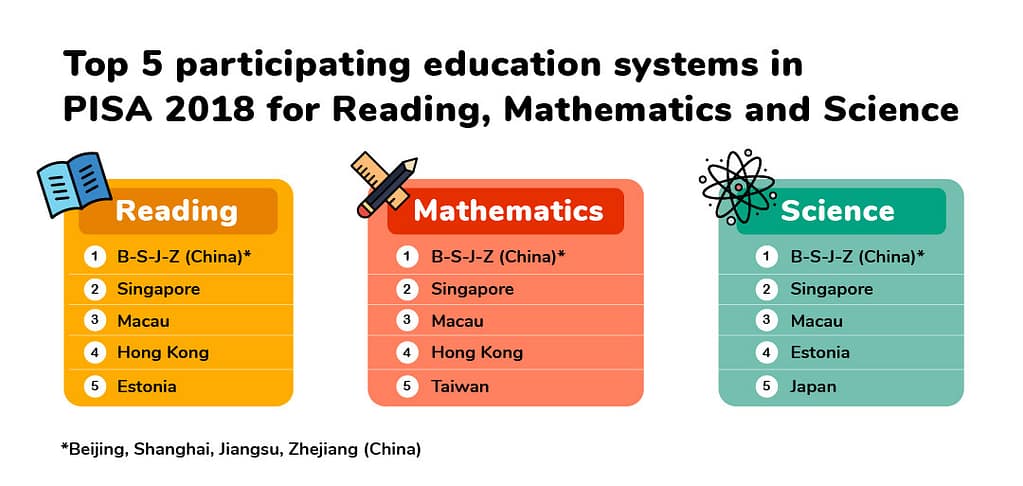

If rote learning doesn’t help learners with problem solving and complex calculations, why do countries like South Korea, Singapore, China, and Japan, which are associated with a more controlled rote learning approach, always rank the highest in the PISA (Programme for International Student Assessment) for scores in math and science?

While rote memorization and critical thinking first appear to be two separate and opposed ways of learning, in fact, the two are linked in a very unexpected way. The link becomes very clear when we consider them in relation to working memory.

Working memory is temporary in nature much like short term memory, however unlike short-term memory, which simply stores information for short periods of time, working memory allows us to manipulate and process information. A good analogy for working memory is as a sort of mental workspace. Think of it as a desk where you can put information that you are working on. In this way our working memory is an essential part of our ability to reason.

The link between critical thinking and working memory is clear.

Greater working memory allows us to have a better capacity to perform mental functions on information. This allows for better problem-solving skills or superior abilities to perform complex calculations. Practice at problem solving and critical thinking can improve our ability to perform these skills by helping us learn better strategies for thinking through problems, but it is not seen as having the impact of actually increasing working memory capacity.

How does rote memorization affect our working memory?

The answer to this question is slightly more surprising. Going back to the analogy of working memory as workspace, if your workspace is limited then leaving all of the information laid out will limit how much new information can be processed on it. When rote learning has This frees up more space for other information to be handled. In this way, having basic mathematical knowledge memorized and automatized uses up less of. Be performed on a simpler function, for example, multiplication tables, the information then requires less space on the workspace . our working memory when performing calculations which can then be used for more complex problem solving.

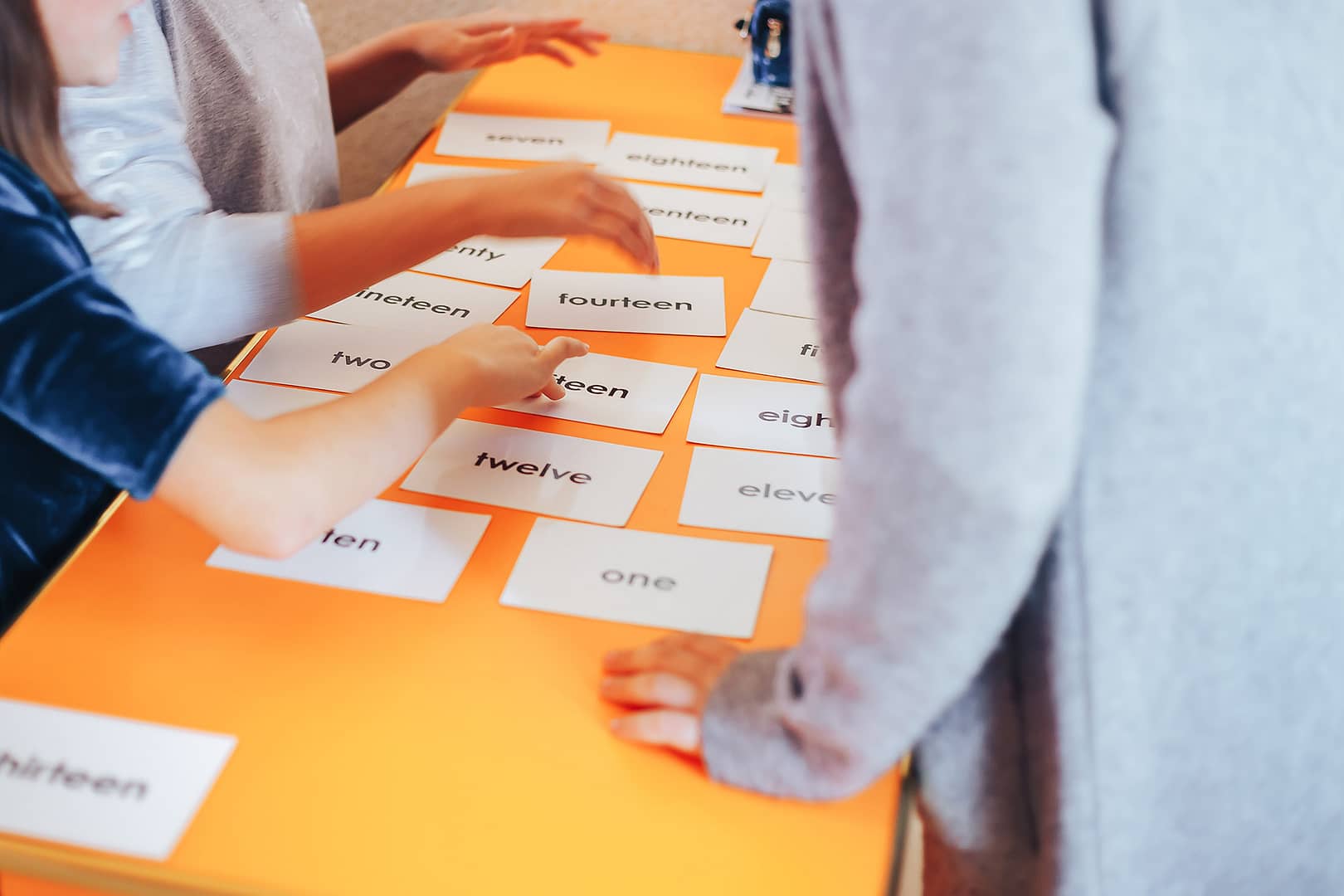

But how does this relate to the learning of language?

The cognitive theory of second language acquisition sees the brain as being similar to a computer. Processing language whether it is to understand a piece of writing or to communicate something verbally puts a burden on the brain’s processing ability. As we practice different language items, they Become more and more automatic. As a result, they require less processing power to execute. This frees up more processing power to deal with newer language items.

The brain is similar to a computer (cognitive theory of second language acquisition)

This indicates that rote memorization of vocabulary and grammar structures is an effective way to learn a language, but it is leaving out part of the picture.

Memory is a fluid and dynamic process. Once we have memorized a piece of information so that we can remember it beyond a couple of minutes it is in our long-term memory. This does not however mean it cannot be forgotten. Continued review of the information can certainly help to solidify the information in long term memory, but the information will still have limited connections to other information in our cognitive schemata. As a result, the information is not quickly retrievable and ready for use spontaneously.

Using a language requires a lot of spontaneous retrieval of information. When speaking or listening in a foreign language our brains are constantly retrieving language knowledge. The act of retrieving this knowledge also poses a cognitive burden. Words that may have been memorized and reviewed can take. .. .as long as a few seconds to retrieve and completely take up the brains processing bandwidth.

It is through using language in different contexts that the language knowledge forms more connections in the brain and the neural pathways for retrieving it become more well established. Every operation our brain preforms that involves a particular piece of language knowledge helps this process. For this reason , language knowledge that we have needed to recall multiple times to achieve a purpose, whether it is to understand a street sign or to ask for help, becomes retrievable quickly and without significant effort.

Recalling language for use in cognitively demanding tasks in particular builds robust neural networks. Language work that does not require learners to think beyond a surface level will build narrower connections more similar to the type of connections developed through rote memorization.